Developing Planetary Health Metrics

The intensification and expansion of agricultural and food production activities, especially over the last century, have largely contributed to two concurrent and contrasting trends: an unprecedented increase in the extension and quality of human life, and a progressive transformation and destruction of the biosphere natural environment that provides the substratum for human life and civilization to thrive. Alarmingly, a growing body of scientific evidence supports the idea that, by exploiting the biosphere natural resources beyond its carrying capacity, humanity may have been mortgaging the health of future generations to realize economic and development gains in the present.

The recently published report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health makes a compelling case for the adoption of a global health perspective encompassing not only human health and wellbeing but also the effect of human activities on the environment. This raises the question of how planetary health should be measured. In fact, metrics capturing changes in human health and in the biosphere capacity to support it are necessary to determine acceptable trade-offs and monitor progress.

However, short- and long-term health effects of changes in the biosphere may differ quite significantly, and are difficult to assess and compare. For instance, a worldwide increase in wild fish consumption would most likely have a positive effect on population health in the short-term, but would probably reduce the availability of several fish stocks in the medium- and long-term, potentially depriving future generations of the health benefits of eating fish. Conventional metrics used to monitor global population health (e.g. the Disability Adjusted Life Year, or DALY, and the Health Adjusted Life Years, or HALY, used in global burden of disease studies) only quantify the health of humans currently living on the planet. It is therefore necessary to identify a new metric capturing also the environmental capacity to support healthy humans in the future.

Recognizing the preponderant impact of food production activities on the health of humans and on environmental degradation we propose the development of a metric framework that quantifies the combined impact of human activities on present human health and on the planet capacity to adequately feed humans in the future. It can be developed adding a new component to a standard global health metric (such as the DALY): the Disability Adjusted Nutrient Year (or DANY). The DANY is a measure of forgone opportunity to produce the essential nutrients required to support a population group in the future, and keep it as healthy as today average world population. This quantity depends on the difference between the nutrients that could be produced with the resources currently used for food production, and the nutrients that could be produced using an equal or smaller amount of natural resources, not exceeding the safety threshold values (i.e. what is considered safe to use based on the available scientific evidence), assuming that state-of-the-art environmentally friendly technology and practices were adopted. It captures two concurrent causes of excessive claim on natural resources: first, the high demand for food products, depending on population needs and market mechanisms, and second, the inefficient conversion of natural resources into nutritious food, depending primarily on technology, practices, and regulations. For instance: current global meat production (about 300 Million tons per year) is generally considered unsustainable because of its high impact on soil, water resources, and the atmosphere. Nevertheless, several studies suggest that it might be sustainable if better practices and technology were adopted. That would include, among others: using high yield feed crops, rotating crops, better irrigation systems, better housing of animals, and improved management of manure. Conversely, because of global population growth, current per-capita rates of meat consumption would probably remain unsustainable even if the best available farming technologies and practices were widely adopted.

Calculating DANYs requires a multidisciplinary R&D effort, and involves collecting, collating, analyzing, modeling, and interpreting data from a wide range of sources, and related to a wide range of topics, including: the carrying capacity of natural environments; the definition of human dietary requirements; the dietary preferences and the elasticity of substitution of food products; the definition and implementation of best practices in agriculture and food processing; the environmental and economic impact of food import/export; the distribution of health and economic benefits and risks across the population; and several ethical issues surrounding time trade-off choices (e.g. how much should we give up today to the benefit of future generations?). The majority of data are obtainable from Food Industry and Agribusiness, international and national agencies, peer-reviewed literature, and NGOs.

The new composite metric obtained summing up DALY and DANY, which could be called Sustainable-DALY (or SDALY), captures the impact of human activities on the health of living humans and on the future viability of healthy human life on Earth. It could be immediately tested as a "one-health" metric, encompassing both human and farmed animal health, before being expanded and adapted to capture more complex inter-temporal relationships between human health, agricultural activities, and the environment. Eventually it can be used to monitor trends, determine acceptable trade-offs, and quantify policy impact.

The intensification and expansion of agricultural and food production activities, especially over the last century, have largely contributed to two concurrent and contrasting trends: an unprecedented increase in the extension and quality of human life, and a progressive transformation and destruction of the biosphere natural environment that provides the substratum for human life and civilization to thrive. Alarmingly, a growing body of scientific evidence supports the idea that, by exploiting the biosphere natural resources beyond its carrying capacity, humanity may have been mortgaging the health of future generations to realize economic and development gains in the present.

The recently published report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health makes a compelling case for the adoption of a global health perspective encompassing not only human health and wellbeing but also the effect of human activities on the environment. This raises the question of how planetary health should be measured. In fact, metrics capturing changes in human health and in the biosphere capacity to support it are necessary to determine acceptable trade-offs and monitor progress.

However, short- and long-term health effects of changes in the biosphere may differ quite significantly, and are difficult to assess and compare. For instance, a worldwide increase in wild fish consumption would most likely have a positive effect on population health in the short-term, but would probably reduce the availability of several fish stocks in the medium- and long-term, potentially depriving future generations of the health benefits of eating fish. Conventional metrics used to monitor global population health (e.g. the Disability Adjusted Life Year, or DALY, and the Health Adjusted Life Years, or HALY, used in global burden of disease studies) only quantify the health of humans currently living on the planet. It is therefore necessary to identify a new metric capturing also the environmental capacity to support healthy humans in the future.

Recognizing the preponderant impact of food production activities on the health of humans and on environmental degradation we propose the development of a metric framework that quantifies the combined impact of human activities on present human health and on the planet capacity to adequately feed humans in the future. It can be developed adding a new component to a standard global health metric (such as the DALY): the Disability Adjusted Nutrient Year (or DANY). The DANY is a measure of forgone opportunity to produce the essential nutrients required to support a population group in the future, and keep it as healthy as today average world population. This quantity depends on the difference between the nutrients that could be produced with the resources currently used for food production, and the nutrients that could be produced using an equal or smaller amount of natural resources, not exceeding the safety threshold values (i.e. what is considered safe to use based on the available scientific evidence), assuming that state-of-the-art environmentally friendly technology and practices were adopted. It captures two concurrent causes of excessive claim on natural resources: first, the high demand for food products, depending on population needs and market mechanisms, and second, the inefficient conversion of natural resources into nutritious food, depending primarily on technology, practices, and regulations. For instance: current global meat production (about 300 Million tons per year) is generally considered unsustainable because of its high impact on soil, water resources, and the atmosphere. Nevertheless, several studies suggest that it might be sustainable if better practices and technology were adopted. That would include, among others: using high yield feed crops, rotating crops, better irrigation systems, better housing of animals, and improved management of manure. Conversely, because of global population growth, current per-capita rates of meat consumption would probably remain unsustainable even if the best available farming technologies and practices were widely adopted.

Calculating DANYs requires a multidisciplinary R&D effort, and involves collecting, collating, analyzing, modeling, and interpreting data from a wide range of sources, and related to a wide range of topics, including: the carrying capacity of natural environments; the definition of human dietary requirements; the dietary preferences and the elasticity of substitution of food products; the definition and implementation of best practices in agriculture and food processing; the environmental and economic impact of food import/export; the distribution of health and economic benefits and risks across the population; and several ethical issues surrounding time trade-off choices (e.g. how much should we give up today to the benefit of future generations?). The majority of data are obtainable from Food Industry and Agribusiness, international and national agencies, peer-reviewed literature, and NGOs.

The new composite metric obtained summing up DALY and DANY, which could be called Sustainable-DALY (or SDALY), captures the impact of human activities on the health of living humans and on the future viability of healthy human life on Earth. It could be immediately tested as a "one-health" metric, encompassing both human and farmed animal health, before being expanded and adapted to capture more complex inter-temporal relationships between human health, agricultural activities, and the environment. Eventually it can be used to monitor trends, determine acceptable trade-offs, and quantify policy impact.

DALY vs. DANY

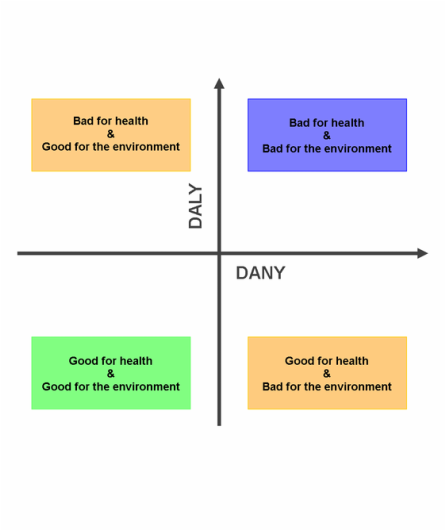

As shown in Figure 1, the effects of human activities on the health of humans currently living on Earth (measured with DALYs) may differ from the effects on future generations, mediated by the environment and measured with DANYs.

Examples:

1-Increasing the use of legumes (combined with cereals) in human diet may reduce the need for protein-rich animal products, and reduce the use of nitrogen fertilizers. That would most likely carry substantial benefits for both the environment (reducing DANYs) and human health (reducing DALYs).

2- A drastic generalized reduction in wild fish capture worldwide would have a positive impact on the environment (reducing DANYs), but would most likely result in a negative impact on health (increasing DALYs), unless appropriate food substitutes are supplied to, and purchased by consumers.

3- Conversely, a substantial increase in wild fish consumption would probably have health benefits (reducing DALYs), but might compromise future availability of fish (and therefore increase DANYs).

4- A generalized increase in red meat consumption in high- and middle-income countries would have a negative impact on both health (increasing DALYs) and the environment (increasing DANYs).

As shown in Figure 1, the effects of human activities on the health of humans currently living on Earth (measured with DALYs) may differ from the effects on future generations, mediated by the environment and measured with DANYs.

Examples:

1-Increasing the use of legumes (combined with cereals) in human diet may reduce the need for protein-rich animal products, and reduce the use of nitrogen fertilizers. That would most likely carry substantial benefits for both the environment (reducing DANYs) and human health (reducing DALYs).

2- A drastic generalized reduction in wild fish capture worldwide would have a positive impact on the environment (reducing DANYs), but would most likely result in a negative impact on health (increasing DALYs), unless appropriate food substitutes are supplied to, and purchased by consumers.

3- Conversely, a substantial increase in wild fish consumption would probably have health benefits (reducing DALYs), but might compromise future availability of fish (and therefore increase DANYs).

4- A generalized increase in red meat consumption in high- and middle-income countries would have a negative impact on both health (increasing DALYs) and the environment (increasing DANYs).

Terms and Conditions: This page (like other sections of the website www.globmod.com) contains original scientific concepts that entirely and solely belong to GLOBMOD (GLOB MOD SL). Any use in publications, presentations, research proposals, and any other communication or application must be fully acknowledged. Omissions and abuses will be legally prosecuted in the appropriate jurisdictions.